Multi-vitamins vs Veggies

With less nutrition in mass produced, genetically modified veggies, grown using pesticides and herbicides, you might want to grow a few veggies for yourself.

Nutrition in Genetically Modified vs. NON GMO ~ Read more.

Or, you may think that popping a multi-vitamin is a quicker way to achieve nutrition, and get full spectrum coverage. But, do multi-vitamins really provide the nutrition available from veggies?

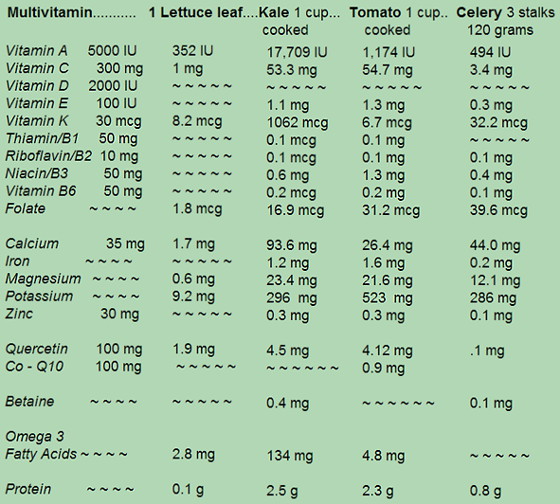

Here’s a chart comparing a multi-vitamin to some commonly grown veggies:

You don’t need the pesticides in grocery veg!

Many people unknowingly consume pesticides on a daily basis. “If you analyse the fruit and vegetables we eat, they’re full of chemicals,” says Serge Przedborski of Columbia University in New York. He adds that traces found in foods accumulate over a lifetime to potentially harmful levels.

In 2006 the Annals of Neurology reported a study of more than 140,000 people that showed Exposure to pesticides – even at relatively low levels – may increase an individual’s risk of developing Parkinson’s disease by 70%. Alberto Ascherio of the Harvard School of Public Health in Boston suggests that non-farmers may have encountered pesticides while gardening.

Less nutrition today In grocery produce

In 2004, a University of Texas research team headed by biochemist Donald Davis, Ph.D., found nutritional declines in protein, calcium, phosphorus, iron, riboflavin and ascorbic acid in plants. The declines ranged from 6 percent less for protein to 38 percent for riboflavin.

There is a temptation, to which I easily succumb, to view organic vegetables as much more nutritious than commercially grown vegetables. In many cases, it’s true, commercially grown are not as rich. But, on the other hand, the use of nitrogen in commercial fertilizer appears to increase phytonutrients, according to Jo Robinson, author of Eating on the Wild Side: The missing Link to Optimum Health.

Jo Robinson’s view is that over the centuries of cultivation, many of our most popular, commonly eaten vegetables have lost nutrition value due to the intense effort to grow more, quicker. As a result, if you choose varieties of vegetables that are more closely related to the original, wild varieties, your nutrient content will be greatly raised.

For instance, choosing a small, red, cherry tomato over a large Beefsteak, provides you with a tomato that is closer to the original wild varieties, and this has more phytonutrition than a larger, highly cultivated variety.

Jo Robinson’s history of the tomato is fascinating and one of many good reasons to buy her book. She notes that tomatoes are native to South America where they were known as “xitomatls”. In 1519 that the Spanish, led by Cortez, found tomatoes and took their seeds back to Spain. By 1692 a cookbook in Naples mentioned tomatoes. Northern Europeans were less enthralled with tomatoes, seeing them as closely resembling deadly nightshade and datura. France, on the other hand loved tomatoes and called them love apples, pommes d’amour. Thus, in 1780 when Thomas Jefferson was serving as US Minister to France he was introduced to tomatoes and brought seeds home to his garden at Montecello. Sadly, Jefferson did not bring home seeds of the descendants of the most nutritious tomatoes, lycopersicon pimpinellifolium which have 40 times as much lycopene as slicing tomatoes we find at the grocery today.

I found lycopersicon pimpinellifolium seeds at Amazon, along with the customary, helpful reviews. While a 20 foot vine may be a bit daunting, giving me pause to appreciate plant breeders reducing the size of the vine, I’m keen to see how these work out.

Last year I discovered that volunteer tomato plants which sprang up in the pot in which I’d grown peas, were ultra healthy and productive. That ties in with Jo Robinson’s comment about commercial use of nitrogen increasing the fertility of vegetables, if fertility and nutrition can be equated. Peas, are nitrogen fixing, meaning that they add nitrogen to the soil as they grow. Broad beans, peanuts and several other culinary plants do the same thing.

Sadly, the peas I planted in the hope of a winter crop, grown indoors, have not done much in the way of springing up.

3/20/2015 ~ This year, about three weeks ago, I planted peas, collards and radishes in a 24″ pot outside on my deck. The lettuce seeded itself.

Last year I tried using a soil mix of composted mulch, ordinary garden soil, and rock dust. The peas appeared to hate it. This year the soil mix contains no composted mulch. Instead it has a lot of coir seed starting mix, which appears to hold moisture better than peat moss.

I planted the seeds quite deep, so that the roots would be nearer the moist soil, than that at the top of the pot which is all too easily dried by our high desert sun.

I’m guessing that in a week I’ll be able to pick fresh lettuce for an on-my-deck lunch.

9/12/2016 ~ I’ve switched to TubTrugs. They don’t take as much space and most plants didn’t need the depth of the Fiskars 24″ pots. Plus, I can put a translucent cover on the TubTrugs in spring to protect seedlings from overnight cold.

6/22/2015 ~ The peas are terrific. I’ve eaten masses of lettuce. The poor radishes got buried under pea and collard foliage.

The peas in the picture are Maestro, I think. The Easy Peasy are shorter and more stout plants, but the peas are equally good. I like the fresh off the plant.

Overall, I prefer snow peas so I can eat the shell and all. Next year. Hopefully I still have my garden next year… I very much hope that Wells Fargo doesn’t take it.

You can see a collard leaf, bottom left, and just above it a carrot’s ferny leaf. I planted carrot seeds among the peas, collards, etc. more as an experiment than in the belief I’d get carrots. But they seem to be thriving.