Gardening gives you fresh, healthy food without pesticides, hopefully. Plus, gardening relieves stress and provides some exercise. If you’ve got things, “bottled up inside” then bottled vitamins may not be the solution. Fresh garden vegetables and fruits are much better on several levels.

If you’re taking a multi-vitamin, look at a chart comparing a few vegetables to a multi-vitamin, in terms of nutrient richness. You may be surprised. See chart.

You also may be surprised to learn that nutrition works better for things like depression, ADHD, etc. than medications.

The surprisingly dramatic role of nutrition in mental health, a TED talk by Julia Rucklidge

Rich Soil for Rich Nutrients

Your garden vegetables need rich soil to produce food that’s rich in micronutrients. Adding compost and trace minerals to your soil strengthens your vegetables and you when you eat the vegetables. I add a very small amount of Azomite to my soil for trace minerals. When I added a lot, on the misguided theory that more is better, my peas were stunted and didn’t produce at all.

Vegetable Costs

Say you mostly shop for vegetables. In that case, the cost of organic may put you off. I mean, how bad can commercially grown, mass produced vegetables be? A GMO vs Non-GMO chart shows that when Glyphosate is used to ensure a “good” crop, nutrition nose dives. View chart.

Some Vitamins are Unrelated to Plants

Some vitamins don’t come from plants, but by growing your vitamins you will get these vitamins as a bonus. How’s that work? Basically, vitamin D comes from sunshine on our skin. Our bodies make vitamin D with as little as 10 to 20 minutes of sunshine on skin. So, when you garden outside in the sunshine, you give your body the sunshine it needs to make vitamin D.

Astaxanthin gives flamingos, shrimp, lobsters their red coloring

But, Sunburn? Have you ever been “red as a lobster”? If so, you know full well that sunburn is a legitimate concern.

Every year for many years I got sunburned when the weather improved enough for me to start gardening. But, no more! How did I stop getting sunburn? To my surprise, Astaxanthin, a supplement derived from algae, protects against sunburn, and surprisingly enough, it’s related to lobsters: it’s what gives them their red coloring. Astaxanthin Health Benefits ~ Read more.

When I read Astaxanthin reviews I was not convinced that Astaxanthin could prevent sunburn, but I ordered it anyway, for it’s excellent anti-oxidant properties. It turned out that Astaxanthin does indeed protect against sunburn, which is great because I get my vitamin D from the sun as long as I don’t use sunscreen. Happiness!!!

About vitamin Content

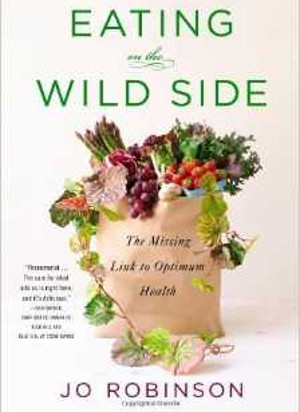

I was surprised to read in an interview with Jo Robinson, author of Eating on the Wild Side, that many commercially grown food plants provide more vitamin content than organically grown counterparts. It turns out, according to Robinson, that commercial growers use more nitrogen fertilizer than do organic growers, with the result that commercial plants have a higher vitamin intensity.

From my experience, I know that tomatoes I grow in a pot previously used in the spring for peas, are stronger and more fruitful. So, I’m a nitrogen believer. Peas, you see, are “nitrogen fixing” ~ they add nitrogen to the soil.

Jo Robinson’s main point, however, is that early forms of different food plants were richer in nutrition than plants that evolved as we searched for bigger, more uniform plants and vegetables, with smoother skin (hiding a lack of nutrition within).

Enrich soil in with spring peas

Since peas are happy in cool, if not cold weather, you can enrich your soil by planting peas before you plant other vegetables or annual flowers.

Not everyone subscribes to the simple nitrogen fix theory, however. There are those who doubt, with some legitimacy, saying that it is not the pea plants themselves, or whatever legume you chose for its nitrogen fixing properties, that put nitrogen into the soil, rather, it is nitrogen fixing bacteria.

The bacteria that fix nitrogen, called rhizobium, work in symbiotic union with legumes and have developed with legumes over centuries, so if your garden is in an area, like Northern Europe, where the legumes first developed, then your garden is going to be rich in rhizobium and your pea plants or broad beans, or whatever legumes you grow, will enjoy all the joys of nitrogen fixing. Else, not so much.

Now, I know my tomatoes did better when they were planted where I’d previously grown peas, so I’m certain there were rhizobium in the soil, most likely as a result of coming with my pea seeds.

Since I live in New Mexico which is far from Europe I can only believe that the necessary bacteria are in my soil in some small amount, which may increase when they are given the peas or other legumes with which they love to grow.

Actually, beans come to mind. Beans are a native New Mexico plant and a legume, so perhaps native beans have enriched our local soils with rhizobium, even though our soil is highly clay and not loamy as so many gardens in Europe tend to be, as a result of careful tending over centuries.

Mycorrhizae

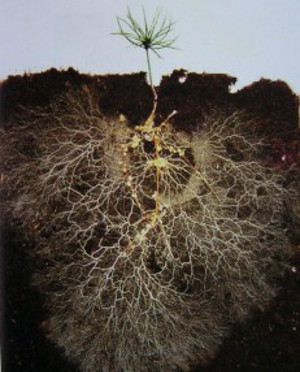

Similar to rhizobium and legumes, but different, is the effect of adding mycorrhizae to your soil.

The Atlantic ran an excellent piece on mycorrhizae: Healthy Soil Microbes, Healthy People. David Read’s photograph, accompanying the piece, gives a good view of what goes on out of sight, deep in the soil. Goes on, that is, if we have healthy microbes and healthy soil.

When The Atlantic published the piece on soil I quoted parts in tweet after tweet. My feeling is that many people don’t have the time or inclination to read an entire piece, but if given the salient points, they may use them and even pass them on.

The piece began by pointing to similarities between how we’ve treated the food processing part of our bodies, and how we’ve treated the food processing area of plants.

Just as we have unwittingly destroyed vital microbes in the human gut through overuse of antibiotics and highly processed foods, we have recklessly devastated soil microbiota essential to plant health through overuse of certain chemical fertilizers, fungicides, herbicides, pesticides, failure to add sufficient organic matter (upon which they feed), and heavy tillage.

Soil bacteria and fungi serve as the “stomachs” of plants. They form symbiotic relationships with plant roots and “digest” nutrients, providing nitrogen, phosphorus, and many other nutrients in a form that plant cells can assimilate.

An astonishing part of the piece talks about how plants communicate with one another via the mycorrhizae threads that attach to their roots. It cites a study done in the U.K. in which broad bean plants were found to alert other broad bean plants of the coming of aphids. The broad bean plants that received the early warning were able to produce defensive chemicals that attract wasps, which eat aphids. Another study showed that tomato plants warn each other via mycorrhizae filaments.

There are researchers who believe that the alarming increase in autoimmune diseases in the West may be due to disruption of the ancient relationship between our bodies and the microbial symbionts with whom we coevolved. A symbiont is one member of a symbiotic relationship in which different species live together to their mutual benefit, and in some cases cannot go on living in the absence of the other member.

It turns out that the soil, or more precisely, the microbes in soil, play a part in our climate. Really:

With regard to stabilizing our increasingly unruly climate, soil microorganisms have been sequestering carbon for hundreds of millions of years through the mycorrizal filaments, which are coated in a sticky protein called “glomalin.” Microbiologists are now working to gain a fuller understanding of its chemical nature and mapping its gene sequence. As much as 30 to 40 percent of the glomalin molecule is carbon. Glomalin may account for as much as one-third of the world’s soil carbon — and the soil contains more carbon than all plants and the atmosphere combined.

It’s exciting to think that we can grow our own vitamins, that we can enrich our soil with living microbes that enrich our plants with nutrients they need, but can’t get on their own.

Healthy food plants provide us with phytonutrients which are naturally occurring chemical compounds, usually most prevalent in the skin, stalk, and seeds of plants. There are thousands of different ones, of which only a small number are made familiar to us through publications and, primarily, Pharma’s use of them in profitable products. For instance, we’ve heard of reservatrol from grape seed, beta-carotene from orange and red vegetables, like carrots, and bioflavinoids.

But for each named phytonutrient in a fruit or vegetable, there are hundreds whose names are not incorporated into supplements we can buy to improve our health.

What a trade off it is, to eat grapes for their nutrients, when at the same time grapes are one of the most heavily chemically treated crops: pesticides, herbicides, etc. Similarly, apples with all their lore, “An apple a day keeps the doctor away,” are now laden with pesticide and herbicide. Commercial growers have indeed increased production and made crops available over a far larger portion of the calendar year, but at what cost? The apples look wonderful. The grapes often look dusty, inviting a good rinse, or wash. But inside these once rare treats, there is a growing rarity of healthy nutrition.

If you watched The Tudors, you may have noticed that apples were there for the king, not so much for his peasant subjects.

Today apples are readily available in grocery stores, but their healthy properties may not be nearly as common as they once were.

The Sound of Tree Rings